In Pursuit of Peace

Building Police-Community Trust to Break the Cycle of Violence

Editor’s note: This report was originally published January 2020 and updated September 2021.

The vital nonfiction work Ghettoside opens with a detective returning a pair of shoes.

The detective steps into a small living room crowded from wall to wall with photos, trophies, awards, and stuffed animals—mementos to a murdered boy named Dovon. The boy’s mother greets the detective wearing a loose t-shirt with Dovon’s face printed on the front, and gets choked up at the sight of her son’s shoes. They had been held in an evidence locker for nearly a year after Dovon was shot in the head by another boy at a bus stop at the age of 15.

The mother has diabetes and her doctor has been urging her to get out and walk more. But Dovon was shot to death just a few blocks away, and she has been too frightened to leave her home. Instead, she spends many days lying in the dark, unable to will herself to move or speak.

When the detective hands the mother her son’s shoes, she takes them into her arms and leans back against the wall. She slowly lifts one shoe to her face and presses the open top against her mouth and nose, desperate for a trace of her son. She inhales the shoe’s scent with a long, deep breath, closes her eyes, and sobs. Her knees give out; she slides down the wall and collapses to the floor, her face still pressed into the shoe of her dead son.

A year before, she had dragged the detective to Dovon’s bedside at the hospital, determined to make him see her son as more than an anonymous statistic. “I want you to meet him,” she told the detective. “I want you to see his face.” And he did.

Photo by Matt McClain/The Washington Post via Getty Images

The hard truth, though, is that we—our nation, our politicians, our media, our laws, law enforcement, our justice system, and our national movement against gun violence—have overlooked and failed families like Dovon’s with catastrophic frequency and consequence. Murder commonly leads the local evening news, and our TV dramas, podcasts, and books are filled with stories about mass violence, cold cases, and celebrity homicides.

Yet too often, our society turns a blind eye to the ways murder typically impacts American families and life. It too easily ignores the raw agony that shootings impose on the thousands of Americans every year who are left, ravaged by grief, to collect their loved ones’ shoes.

Introduction

Executive Summary

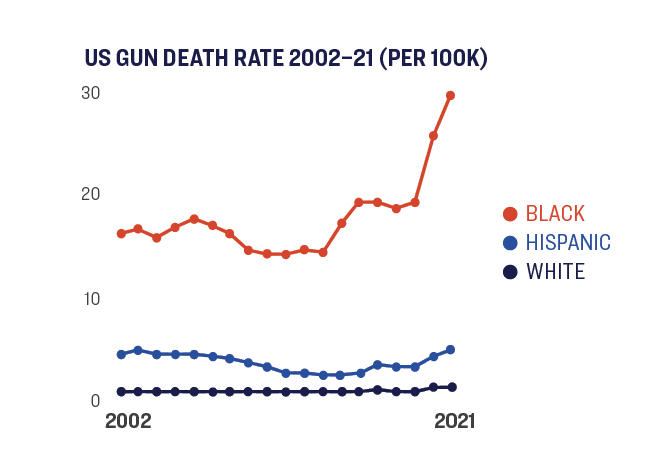

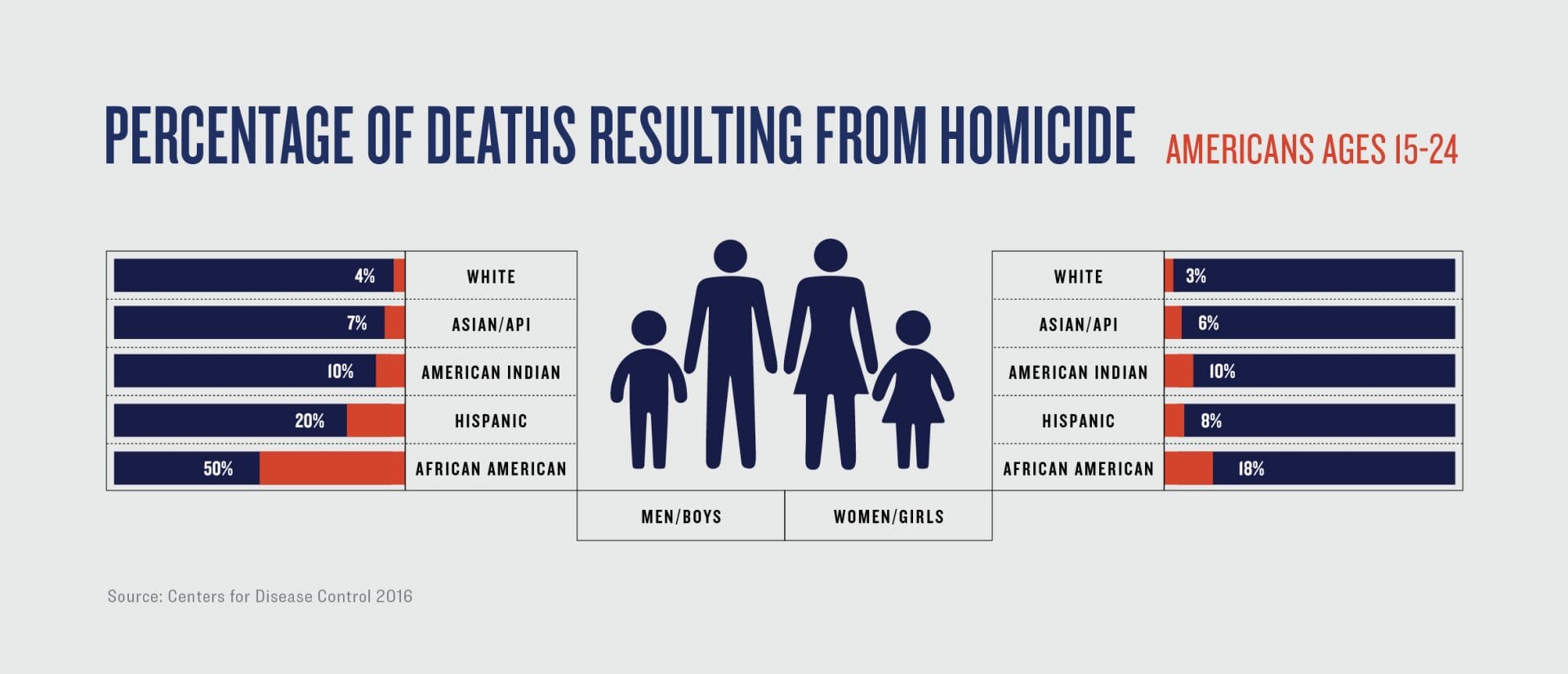

It is not possible to talk meaningfully about gun violence’s devastating impact on our country without talking very specifically about racial inequality, because a large majority of those empty shoes belonged to men and boys of color. In 2019, the parents of a Black teenage boy like Dovon were as likely to lose their son to gun violence as nearly every other cause of death combined.1 More than two thousand Black teenage boys died in the United States that year: 258 (12%) were killed in motor vehicle or traffic accidents; 211 (9%) died by suicide; 61 (3%) died of cancer, and 1,097 (49.4%) were murdered, nearly all of them (1,068) killed with a gun.

This crisis is one of the starkest examples of racial inequality in America today: in 2019, homicide was responsible for 5% of deaths among young white men and boys aged 15 to 24,2 a number that would be unheard of in nearly every other high-income country on earth.3 But homicide was responsible for 13% of deaths among Indigenous or Native American men and boys, 17% of deaths among Hispanic or Latino men and boys, and nearly half, 48%, of deaths among Black men and boys in this same age group.4 Nearly all of these young lives were taken with guns. For many communities of color, especially for young Black men and boys and their loved ones, shootings are not just a leading threat. They are the threat that dwarfs all others.

This catastrophic loss of life is undoubtedly the result of policy failures. Reckless and profit-motivated gun laws have flooded our communities with increasingly lethal modern weaponry, easily accessible to people with histories of violence and hate. Federal law has effectively hindered law enforcement’s ability to investigate the gun industry and traffickers profiting from murder epidemics. Many states have prevented their cities from regulating the carrying of weapons in public streets and spaces. At the same time, leaders in most jurisdictions have largely failed to invest in effective community-based violence intervention and prevention programs.

But it’s also time for the gun violence prevention movement to recognize that our country’s failure to protect so many Americans from murder is a failure not just of policy, but also of policing and the justice system. To understand the devastating toll that gun violence takes on our poorest and most segregated communities, we must address the priorities, strategies, and effectiveness of those public agencies tasked with protecting and serving all of us.

The status quo is failing so many, and the stark choices presented by TV talking heads and in much of popular culture—between policing that is just and policing that is effective—are false choices. The evidence is clear: community-oriented policing that builds community trust and participation, prioritizes accountability and harm reduction, and refocuses law enforcement time and resources on protecting people and solving homicides is effective at preventing cycles of violence.

This report touches upon broad, interwoven topics—inequality, racism, poverty, policing, and guns—but its premise is simple: police-community trust is a gun violence prevention issue.

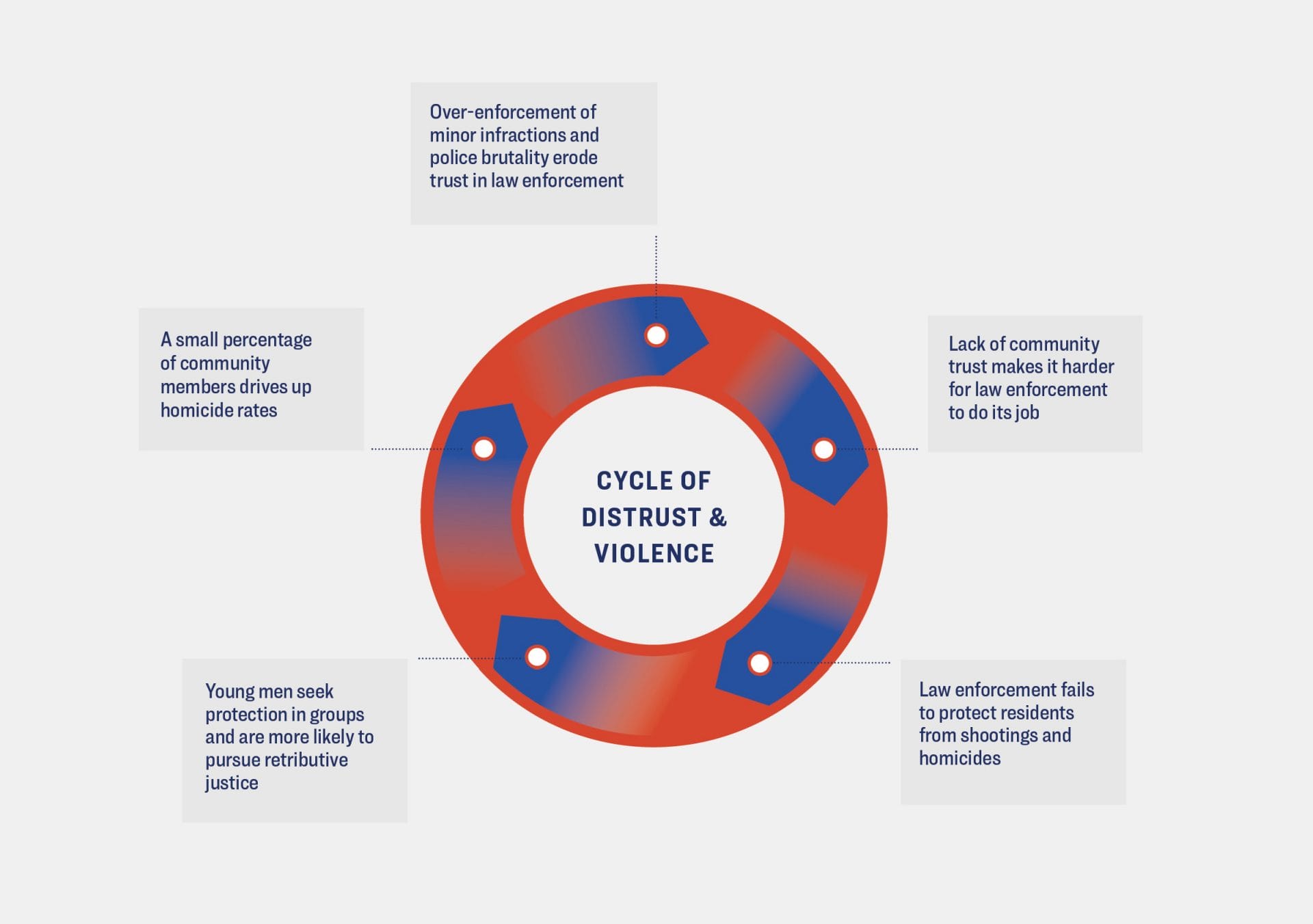

To deliver public safety and protect people from shootings and murder, law enforcement agencies need active cooperation from the communities they are meant to serve. The research, and the recent experience of many of our nation’s cities, show that when police departments lose this trust, a dangerous, downward spiral of disengagement ultimately leads to spikes in violence and vigilantism that threaten the safety of residents and officers alike.

This downward spiral occurs when community members’ distrust of law enforcement deepens, witness cooperation and engagement with officers diminish, policing becomes less informed and less effective, more shootings and murders go unsolved and unpunished, and more people seek vigilante justice in the streets. Fear and gun carrying spread like a contagion and make everyone in the community, including the police, toxically stressed and quicker to pull the trigger. And both the community and law enforcement become more cynical about the other’s motives and worth.

All of this creates a continually destabilizing feedback loop of distrust, disengagement, and fear that can leave whole communities scarred by the violence of a desperate few.5

And so, to meaningfully address our gun violence crisis, we must understand how cycles of distrust and cycles of violence work. We must understand that a deep, generational lack of faith in law enforcement has kept many Americans from actively engaging with their police force—or even calling 911. We must understand that one of the most dangerous things a police force can do, for both its officers and citizens, is to lose the trust and partnership of the community it serves. And we must understand that building earned and durable trust between communities and law enforcement is critical to stopping shootings and saving lives.

Police-community trust is a gun violence prevention issue.

Our aim in this report is to explain why, as a gun violence prevention organization, we must be engaged as allies in efforts to build community trust, reform harmful policing practices, and refocus public safety efforts around just, effective, and proactive responses to community violence. While a comprehensive plan for criminal justice and police reform is beyond this report’s scope, Giffords will continue to publish research and analysis about this and other topics related to the intersection of gun violence, policing, and the administration of justice, as well as expand our efforts to support partners and allies who have been doing important work in this space for years, including the National Network for Safe Communities, Faith in Action, the Urban Institute, the Urban Peace Institute, the Community Justice Reform Coalition, Cities United, and the National Police Foundation.

This report condenses the leading recent research in the field to explain how cycles of distrust and disengagement fuel cycles of violence—to show how police officers’ brutalization of one man in Milwaukee led to increased shootings and homicides across his city for over a year, and how similar patterns of distrust and violence play out in cities around the country with disturbing frequency.

This report also offers the hopeful truth that progress is possible. In 2015, the national blue ribbon Task Force on 21st Century Policing prepared a comprehensive report containing recommendations for law enforcement agencies and policymakers to build trust and better protect our communities. By implementing such reforms and refocusing law enforcement efforts, a number of police departments and community leaders across the country have contributed to meaningful, lifesaving reductions in gun violence in a short period of time.

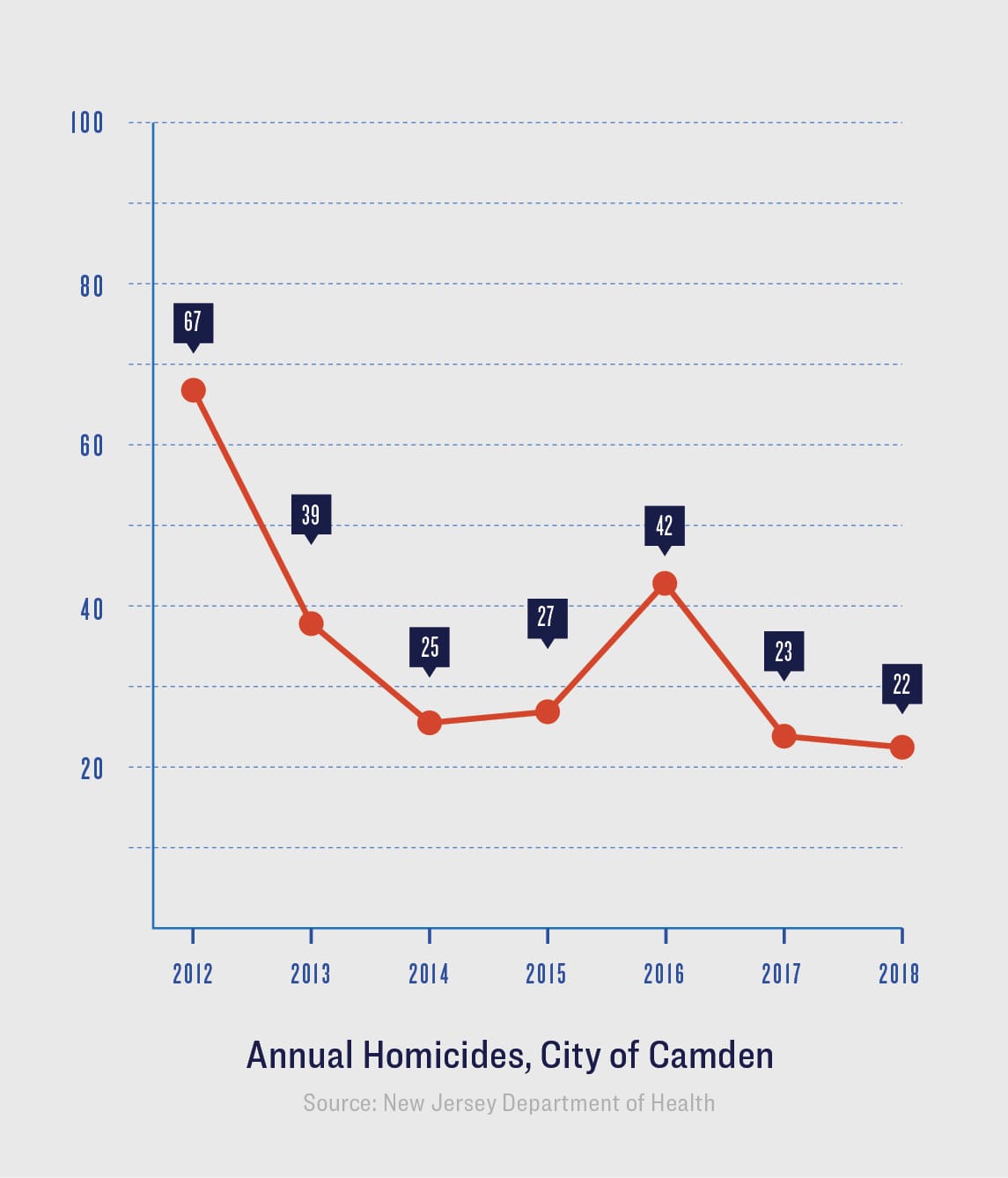

In places like Camden, New Jersey, cities have implemented real reforms, built trust between communities and police, reversed cycles of violence, and saved lives. Camden Police Chief J. Scott Thomson spearheaded an overhaul of his city’s police force that focused on earning community trust, and helped the city achieve a 67% reduction in homicides between 2012 and 2018.6 These and other models described later in the report are examples of progress underway—of lifesaving efforts that are working but unfinished. It is critical that we hold them up as examples of what could be in cities across the country.

Photo by TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP via Getty Images

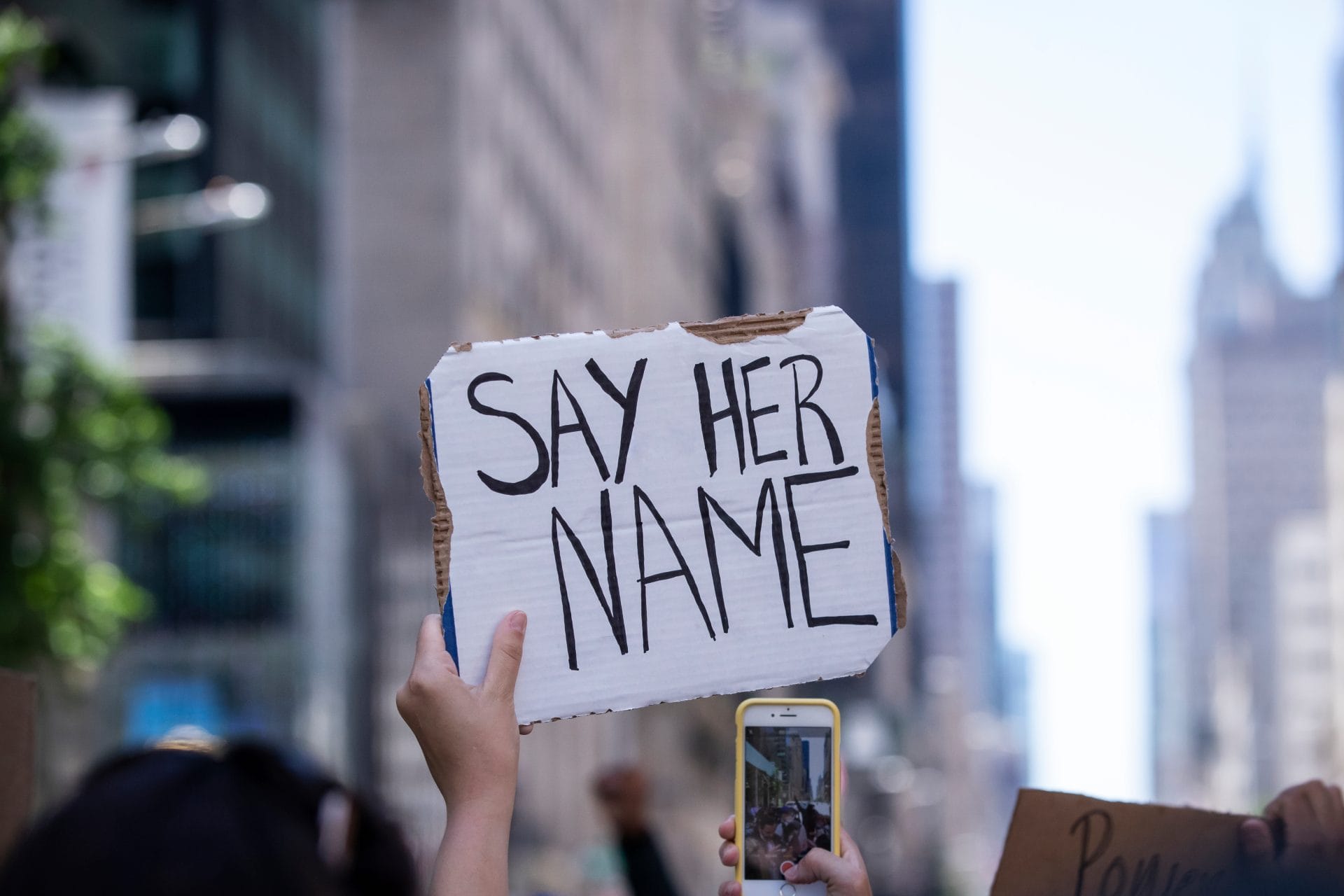

It’s especially important that the gun violence prevention movement speak out now. In May 2020, five months after this report was originally published, 46-year old father of two George Floyd was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Video of his murder captured by a horrified teenaged eyewitness sparked a national outcry, and in combination with news of the killing of other Black men and women—including Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Manuel Ellis, Rayshard Brooks, and so many others—prompted what was likely the largest mass protest movement in US history.7

Millions mobilized and marched with the Black Lives Matter movement, calling for more just and effective approaches to public safety. These protests, and the severe and disproportionately violent law enforcement response they encountered in cities across the country, prompted communities and lawmakers at all levels of government to reexamine policing—from the tactics commonly used by law enforcement, to laws governing oversight and accountability, to the ways in which traditional policing strategies and priorities have failed to protect the life and safety of every person.

Concurrently, 2020 also saw the largest one-year spike in homicides since the US began recording these numbers.8 Though many factors likely contributed to this increase, including a record boom in firearm sales and the economic and emotional instability caused by the coronavirus pandemic, declines in law enforcement’s perceived legitimacy and trustworthiness also likely played a role in this record spike in homicide, as this report will explore in detail.9

The nation has been crying out for action and a considered policy response. In June 2020, Representative Karen Bass introduced the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, a comprehensive measure to reform policing practices, strengthen oversight and accountability mechanisms, and promote transparency and data collection regarding policing and racism in the justice system.10 The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act passed the US House of Representatives in two different sessions, but as of this writing, is still awaiting a vote in the US Senate.

Also awaiting a vote in the Senate is the Break the Cycle of Violence Act, which would make historic and long overdue investments of at least $5 billion in community-driven violence intervention programs that work to proactively heal and protect people at highest risk of violence. These measures would represent critical steps toward reducing harm in policing and the criminal system, transforming ineffective and unjust public safety approaches, and finally, meaningfully addressing the national crisis of gun homicides, especially for America’s young men and boys of color.

Photo by Michael B. Thomas/Getty Images

Murder Misconceptions

In communities where violence is rare, people may imagine that murder and the justice system follow a familiar Hollywood script. A murder occurs; witnesses come forward to share what they know; a detective follows a lead; a perpetrator is identified, arrested, and convicted; a devastated family and community begin to heal. In this script, law enforcement officers are envisioned as combat-ready SWAT team warriors or modern-day versions of Sherlock Holmes with high-tech CSI tools. One study found that across 730 episodes of “Law and Order,” over three-quarters of murder victims were white while only 10% were Black, and nearly every murder led to an arrest and conviction.11

But this Hollywood script is not the story of most murder in America.

In the real world, more than three-quarters of American homicide victims are people of color, and nearly 60% are Black. Large numbers of shootings are never reported to the police,12 not because victims and witnesses don’t feel terrified or outraged, but because they often do not view their police force as capable of or interested in keeping them safe. Nationwide, a majority of Black victims’ killers are never even arrested, let alone convicted.13

For families grieving a murdered or injured loved one in cities across the country, the jarring truth is that the justice system usually fails to deliver justice. It fails to remove people who have taken or threatened human life from their victims’ communities. This reality helps explain why a desperate few decide to take justice into their own hands, meeting violence with violence and fueling cycles of retaliatory shootings that can last for generations.

To be sure, not every perpetrator is also a victim, and not all violence is retaliatory. But for far too long, our country has viewed the overwhelming concentration of shootings and trauma in our poorest and most segregated enclaves as an intractable mystery—or worse, as evidence that whole communities or races of people are tolerant of “thuggishness” or a “culture of violence.” We have often structured our criminal justice and policing priorities around uninformed or racist diagnoses that see entire communities as filled with problems and perpetrators, instead of partners and survivors desperate for both justice and safety.

Traditional policing practices often fail to reflect the reality that most violence is perpetrated by a very small segment of any given community. Recent research has confirmed that even in the neighborhoods with the most gun violence in America, a majority of shootings are perpetrated by people within a small, high-risk population involved with street groups, and that these group members constitute a fraction of 1% of the population. (This research is discussed in greater detail later in this report.)

Well over 99% of the people living in our nation’s cast-off “murder capitals” are survivors and victims of the violence around them—not perpetrators. They are key witnesses to the cycle of shootings occurring outside their doorsteps and key partners in efforts to stop it. But they have to be seen, treated, and protected accordingly.

Our country’s most effective police departments know better than anyone that to be successful in interrupting cycles of community violence, law enforcement officers “must have active public cooperation, not simply political support and approval.”14 They need witnesses to trust them, come forward with information, and risk their own safety by testifying. They need to be able to work closely with community organizations and service providers to intervene and prevent violence before it occurs. They need grieving victims to trust that the justice system will deliver justice and keep them safe, so a desperate few don’t resort to vigilante forms of justice instead.

Many cities’ shootings are public events; they are perpetrated on populated streets to send a retributive message.15 For law enforcement, the task of solving these cases is therefore usually “not a job for Sherlock Holmes”16 or SWAT teams—it is something much more challenging. Homicide detectives frequently struggle to draw out what everyone in a neighborhood already knows but cannot or will not say to them or in an open court. They work on a very personal level to solicit tips and testimony from terrified and distrustful witnesses who have often felt over-policed and under-protected for years. When law enforcement fails to solicit that witness participation, vigilante justice and shootings become much more common.17

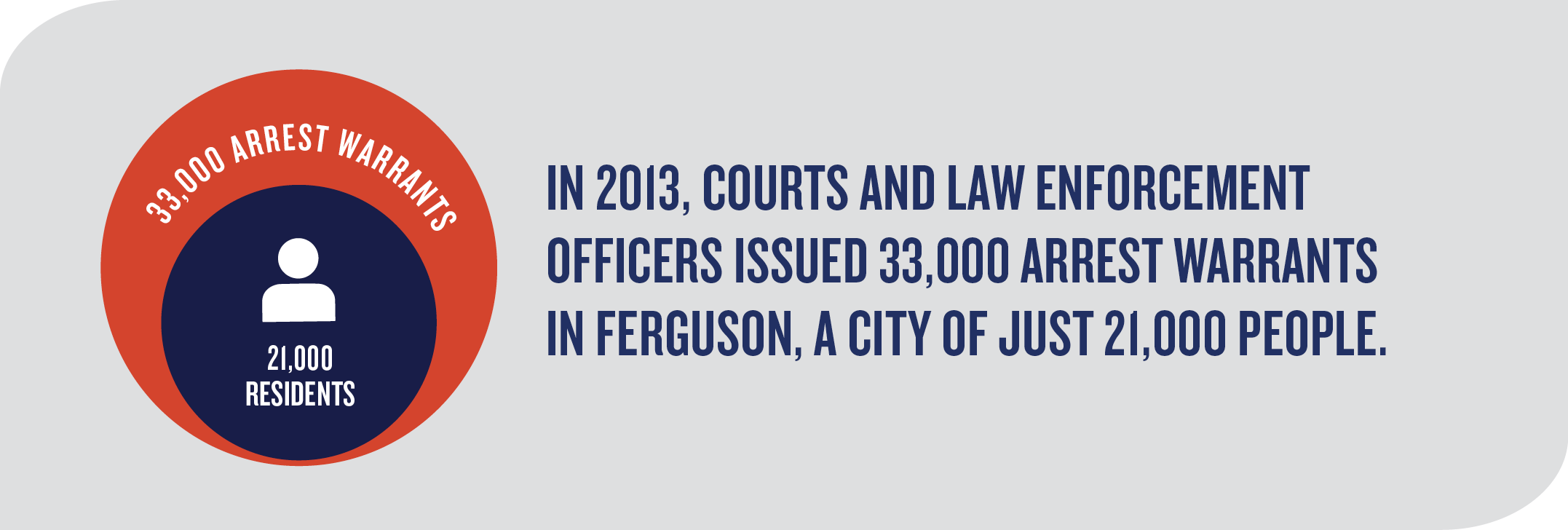

The challenge of soliciting that cooperation is made much more difficult by the state of our justice system—by the fact that many law enforcement agencies prove brutally zealous in enforcement of minor infractions in communities of color, and at the same time powerless to accomplish their most vital public safety task: keeping people safe and alive. Nationwide, our police forces arrest more people for possessing personal quantities of marijuana than for all violent crimes combined.18

Meanwhile, recent analyses estimate that on average, officers in urban police departments spend just 4% of their time responding to serious violent crimes and less than 1% of their time handling homicides and shootings.19 This over-enforcement and under-protection are two sides of the same coin.20 Both devalue the lives and priorities of communities of color, and both reinforce a destabilizing lack of trust that undermines public safety.

This lack of trust means the tangible loss of the information and relationships that actual, non-Hollywood police work is built on—the witness tips, testimony, and partnerships that allow law enforcement to do its job, remove shooters from their victims’ communities, protect those at risk, and replace street justice with formal justice. As discussed further later in the report, in cities across the country, lack of trust in law enforcement has made these partnerships difficult, and both law enforcement and communities bear the consequences.

Gangs Vs. groups

When law enforcement is not trusted to protect and serve a community’s interests fairly and effectively, cycles of community violence and retaliation take root. These entrenched cycles of violence claim an enormous number of lives and also impose both physical and invisible wounds on much larger numbers of people.

Young people in impacted neighborhoods often suffer devastating and traumatic effects from growing up in a climate where life is precarious and they experience chronic exposure to shootings, bloody injuries, and death. Living every day in fear takes a terrible toll.21 More than half of young people exposed to violence suffer some form of PTSD,22 and experts at the National Institute of Justice have noted that “youth living in inner cities show a higher prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder than soldiers” in our wartime military.23 Young people who are exposed to violence can become hypervigilant about their surroundings and perceived threats, and many exhibit severe PTSD symptoms such as disturbed sleep, chronic illness, fatalistic thinking, hopelessness, anger, impulsivity, and feelings of powerlessness.24

Over-enforcement and under-protection are two sides of the same coin.

Despite these adverse traumatic experiences, the vast majority of these young people positively adapt and resiliently persevere, especially with the support of their families or communities.25 As discussed below, the vast majority do not respond to this trauma by perpetrating violence themselves.

Some battle the sense that they are defenseless by taking on roles typically reserved for adult health and safety professionals: in Chicago, teens formed an anti-violence group called GoodKids MadCity, which, among other things, trains other teens on how to tend gunshot victims’ wounds before an ambulance arrives.26 A July 2019 NBC News story about the group featured a 14-year-old boy whose brother, an anti-violence activist in his community, was fatally shot at 19; the boy mentioned that a bystander with emergency training could have saved his brother’s life, and talked about learning how to apply a shoelace tourniquet to his own wounds in case he is shot too.27

Others attempt to battle feelings of defenselessness or powerlessness by carrying weapons, often illegally.28 When the Urban Institute surveyed young people between the ages of 18 and 26 in Chicago neighborhoods with the most violence, they found that young men were 300% more likely to have carried a gun if they had been shot or shot at in the past year.29

Finally, a relatively small number of people choose to battle feelings of defenselessness or powerlessness by joining informal cliques of other young people, usually young men. These groups offer the perception of safety in numbers and the promise of pursuing vigilante justice on group members’ behalf.30 People who have been victims of or witnesses to violence are particularly likely to join these groups.31 Researchers have also found that being shot, shot at, or witnessing a shooting doubles the probability that a young person will commit a violent act themselves within two years.32

In the popular imagination, there is a persistent myth that most “inner city” shootings are perpetrated by large, highly organized, even transnational criminal gangs involved in vicious turf wars around illegal drug markets.33 Some groups do fit that definition and have captured the public’s attention. But in reality, according to leading crime researcher Thomas Abt, “most gangs in the United States are small, informal groups that have limited capacity for highly organized crime.”34

There is also no common definition for the term “gang”—different jurisdictions use different, often subjective terms. In practice, many of the small, informal groups commonly labeled as “gangs” in public discourse are little more than neighborhood cliques of young men of color.35 In other communities, a similar set of young white males whose members hang out together, occasionally get into trouble, and wear the same clothing or varsity jackets as a symbol of group identity might simply be called a “clique,” “crew,” or “fraternity.”

But when group identity reinforces an impulse to escalate confrontations to public violence, these groups can inflict massive harm. Researchers for the National Network for Safe Communities have found that a majority of shootings in American cities are perpetrated by a small number of young men affiliated with such groups. These groups typically operate without any common hierarchy or criminal goals, but their members may identify as a loosely cohesive, self-protective clique, claim control over certain city blocks, and at least occasionally perpetrate violence, often in retaliation for an attack or threat against a fellow group member.36

It is often believed that people affiliate with these groups because they glorify criminality or violence, so policy and policing strategies have often prioritized efforts to combat gang identity as a means of addressing violent crime. But in communities that suffer from rampant exposure to violence, some desperate young people join these groups because they are seeking protection from violence, not running toward it.37

In communities where most shootings go unreported and unpunished, these groups offer the perception of safety and accountability; a research review published by the US Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention notes that “youth most commonly join gangs for the safety they believe the gang provides.”38 These groups are in many ways perceived to be a substitute for law enforcement and the justice system’s failures to deliver justice or safety.39

Yet “the grim reality is that youths who join gangs in pursuit of safety only place themselves in greater jeopardy” as they become targets for retributive violence. As one group member described, “You joined up for self-defense, but then you become the dudes you hated.” Once a young person becomes publicly associated with a group and implicated in cycles of retaliation, he “can never be alone—you always have to be with your people” for safety in numbers,40 even though affiliation with those same people often makes these young men targets for violence.

As a result, violence and fear of violence often engender more of the same. Much of what news reports casually dismiss as “inner-city gang violence” is actually the horrific—yet predictable—application of vigilante justice by cliques of desperate, often violently victimized, and scared young men.

Law enforcement efforts to reduce violence by targeting gang identity therefore often have it backwards: neighborhood boys and men can become much more cohesively linked as a potentially violent “group” when they are united by a real fear of violence. By successfully reducing the threat of violence, rather than trying to directly attack gang membership itself, we can remove the primary impetus for many people to affiliate with these groups in the first place.41

Finally, while a majority of shootings are inflicted by or against group members, it’s important to note that group-related violence also has massive collateral consequences for many people who have no group affiliation whatsoever. Rival groups might treat everyone on a block as a member of the group who claims it, making everyone in the area, especially young men, targets for unfocused acts of retaliation.

Bullets fired at group members also frequently unintentionally kill or maim neighbors who are entirely unaffiliated with them. In July 2019, a shootout between group members erupted at a block party in a public park in Brooklyn, leaving one person dead and 11 injured.42 In these ways, violence perpetrated by a tiny portion of the population clusters in certain areas, harms an astonishing number of people, and kills about as many young Black men and teenagers in this country as every other cause of death combined.

Though the harms of community violence are pervasive and devastating to the physical and mental health of many, only a tiny number of people within the community respond to this trauma and violence by perpetrating violence themselves.43 In communities suffering most from shootings and murders, the vast majority of residents are law-abiding citizens desperate for a just peace in their streets.

The “Culture of Violence” myth

Unfortunately, the myth that shootings erupt in neighborhoods where residents tolerate criminality and violence is pervasive.44 In this “classic subcultural perspective, lower-class communities [are seen to] generate a distinctive moral universe that glorifies and legitimates aggressive behavior, particularly among male juveniles.”45

This narrative is so prevalent that it is sometimes casually reported as fact. In a 2019 report ranking US cities with the highest murder rates, Forbes Magazine suggested, without any further explanation, that Memphis’s high murder rate was related to the city’s “stubborn criminal culture.”46

It is critical to emphasize then that researchers have found that neighborhood rates of “homicide [are] unrelated to resident attitudes toward deviance and violence,”47 and that “residents of disadvantaged neighborhoods are no more likely to tolerate violence than are residents of advantaged neighborhoods.”48 In other words, communities with devastatingly high rates of shootings and murders are no more tolerant of violence than safer neighborhoods, and communities with devastatingly high rates of poverty are no more tolerant of violence than wealthier ones.

This research is bolstered by researchers’ findings that a majority of shootings in our nation’s most impacted cities are perpetrated by a small subset of group members, and that less than 0.6% of the average city’s population is involved with groups.49 It is hard to credibly claim that a dominant culture of violence exists in communities where the population expresses at least as much opposition to violence as other communities and where well over 99% of residents are not involved in groups and do not perpetrate violence.

Even so, this “culture of violence” narrative persists, and is often racialized. Because community violence is disproportionately concentrated within segregated communities of color, a number of public figures have claimed that essential cultural or racial differences are to blame.

In 2016, for instance, a noted criminologist asserted in a book about the history of crime in America that “the [post-World War] black migration to cities, especially the big cities of the north, brought a culture of violence to the urban landscape.”50 He described this as a “black culture of violence.”51 After former president Barack Obama spoke about the shooting of an unarmed young Black man in Ferguson, Missouri, former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani told CNN that the president “should have spent 15 minutes on training the [Black] community to stop killing each other.”52 Former Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel told MSNBC that gun violence is “an urban problem … that gets put in a different value system.” He went on to say that “a piece of this is the culture … part of this is having an honest conversation, given the lion’s share of the victims and the perpetrators are young African-American men.”53

This narrative often crops up in our media too. Fox News host Bill O’Reilly asserted on-air that “[t]here is a violent subculture in the African American community that should be exposed and confronted.”54 A Black Wall Street Journal columnist wrote of community violence, “This is about black behavior. It needs to be addressed head-on. It’s about attitudes toward the criminal justice system in these neighborhoods, where young black men have no sense of … what it means to be black.”55 A former Minnesota congressman told radio show listeners that “African-Americans had an entitlement mentality, leading to violence in the community” and that it is “a cultural problem in the African-American community that is leading to this.”56

This narrative has also permeated gun lobby talking points. In response to an article about the disparate impact of shootings on communities of color, the director of The Firearms Coalition wrote about the need to address “the elephant in the room”: a “criminal culture [that] has been allowed to grow and fester in inner-city communities and has become particularly prevalent and destructive within black and Hispanic sectors of those communities.”57 Various NRATV hosts have urged audiences to “blame minorities for killing each other,”58 suggested that “if [police] really were out to kill black people, [they] would just stay home for a couple of weeks,”59 and asserted “there is plenty of proof that black culture is inherently more violent than other cultures.”60

It is critical that we address these narratives head-on because they are pervasive, destructive, and demonstrably false.

First, we should acknowledge that this “culture” framing is almost exclusively reserved for Black and Brown Americans: white Americans are significantly overrepresented as perpetrators of school shootings,61 various financial crimes,62 drunk driving offenses,63 and abuse of heroin and other opioids,64 but those racial disparities are rarely discussed in the language of cultural deficiency or racial blame.

Researchers have also found no support for the notion that there is “a subculture of violence” tied to race.65 Nationally representative survey data actually indicate that “white [men] are significantly more likely than black [men] to express their support for the use of violence in defensive situations,”66 and otherwise found “no significant difference between white and black males in beliefs in violence in offensive situations.”67

Research has demonstrated that residents in high-crime neighborhoods are more likely to express support for the need to obey the law than residents of safer communities, and that “contrary to received wisdom, African Americans and Latinos are less tolerant of deviance—including violence—than whites.”68 Similar research findings were published in 1974, 1978, 1980, 1994, and 1997.69

The trope that people of color have not been persistently outraged by or mobilized against community violence is also demonstrably untrue.70 Americans of color—particularly Black Americans—consistently express the highest levels of concern about crime, murder, and gun violence.71

A slightly different culture claim—that community violence disproportionately impacts Black families due to the relative prevalence of single-parent households—is also unsupported by the evidence.72 Rates of gun violence have substantially fallen in recent decades (notwithstanding increases since 2014) at the same time that rates of single-parent households have significantly increased.73 Young Black men are both safer today than they were three decades ago and more likely to have grown up in a single-parent household.74 Additionally, contrary to persistent stereotypes, health reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention about American fathers’ involvement with their children found that “black fathers were the most involved with their children daily, on a number of measures, of any other group of fathers.”75

Finally, the culture-blaming narrative also ignores the fact that the communities most impacted by violence have consistently mobilized against that violence. On a per capita basis, the number of community-based organizations “focused on confronting violent crime and building stronger communities” nearly quadrupled between 1990 and 2013,76 as did the number of groups focused specifically on “crime prevention.”77 Research published in 2017 concluded that “the proliferation of [these] community nonprofits” was “among the most important shifts to occur in urban communities over this period,” and estimated that in the average city, the formation of 10 community-based organizations per 100,000 residents led to a 9% reduction in the city’s murder rate.78

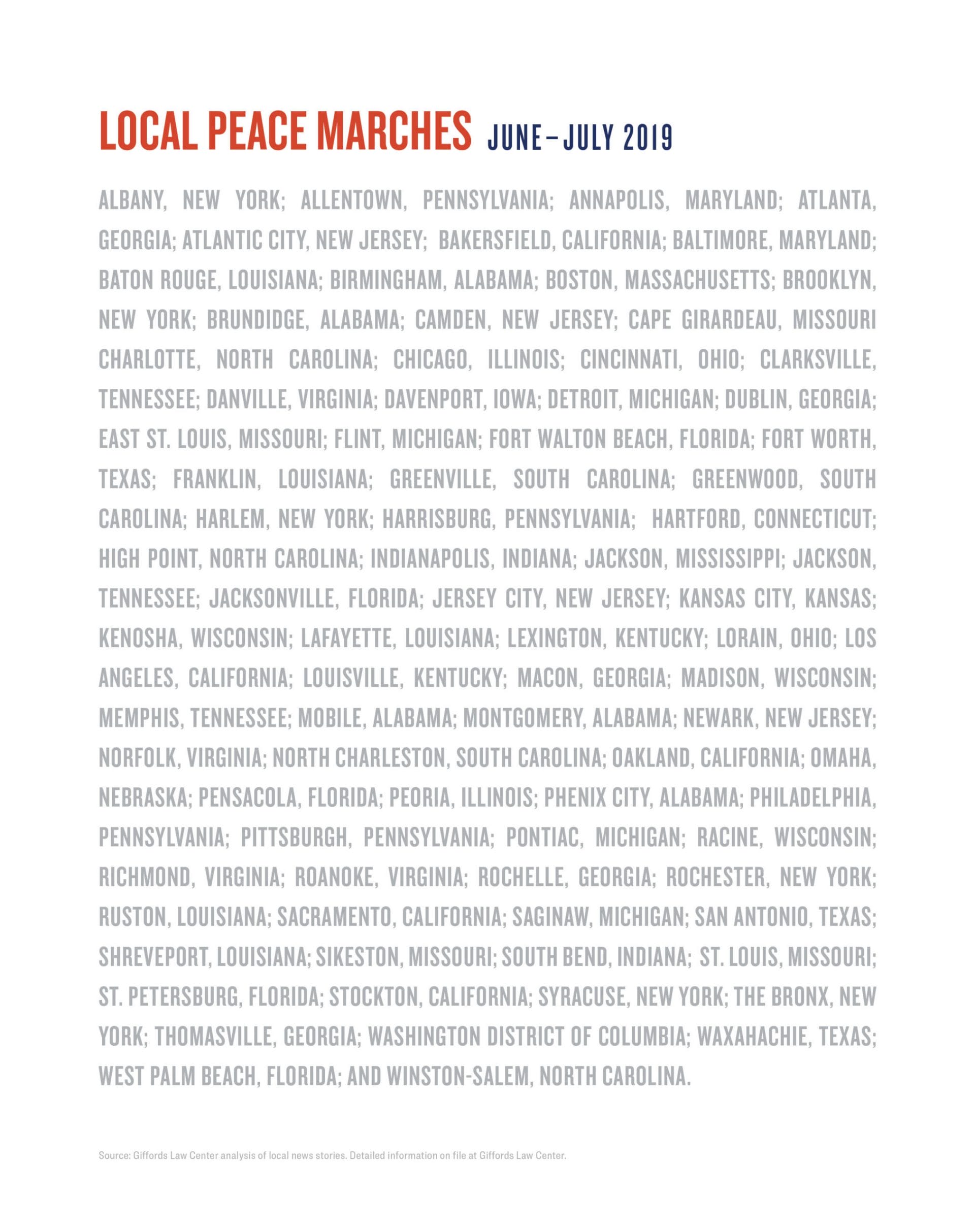

The residents of impacted communities have also mobilized, organized, and marched to call attention to the enormous rates of violence in their communities over and over again.79 Over just a two-month period from June to July 2019, nearly every major city across the United States held locally driven peace marches against community violence.

People suggesting that these communities are not engaged in combating violence in their neighborhoods simply aren’t paying attention. By refusing to accept the status quo and demanding change, these communities have driven reform and improvements for public safety. In Oakland, California, persistent and sustained activism on the part of community groups led the city to implement a series of reforms and invest in a comprehensive violence intervention strategy that led to a nearly 50% reduction in homicides between 2012 and 2018 alone. And as shootings and homicides dropped in Oakland, law enforcement became more effective: homicide solve rates rose from 29% in 2011 to over 70% six years later, suggesting that community trust and partnership were improving too.80

In order to replicate the lifesaving progress seen in Oakland and in other cities explored later in this report, our leaders and law enforcement need to evaluate and correct policing practices that are built around stubborn myths and misconceptions instead of the evidence. Effective public safety strategies reflect the fact that, while gun violence harms every community, shootings in America are overwhelmingly clustered within small areas of our cities, particularly among small numbers of desperate and terrified young men involved in cycles of group violence and retaliations.

Photo by Erik McGregor/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images

Understanding Murder Inequality

To craft more just and effective public safety strategies, we must be clear about how gun violence affects us and who its victims typically are. Some of the most effective violence reduction initiatives in the nation, like the group violence intervention strategy,81 are built in part on data-driven and community-oriented preventative policing. This strategy focuses on protecting the relatively small number of people and places at highest risk and working with community partners to prevent violence among groups engaged in cycles of retaliatory shootings. These strategies effectively refocus public safety and preventative resources on the relatively small number of places and people at highest risk, and reflect these critical but often misunderstood facts about shootings in America:

First, shootings are overwhelmingly concentrated in small geographic areas within our cities.

Second, victims of community violence shootings are overwhelmingly young people of color and especially young Black men, for whom violence is by far the leading cause of death.

And third, most shootings are perpetrated by a tiny high-risk subset of the population involved with groups, which constitute far less than 1% of the population, even in neighborhoods with the highest rates of violence.

neighborhood concentration

The US leads high-income nations in gun violence

Source

Mohsen Naghavi, et al., “Global Mortality from Firearms, 1990–2016,” JAMA 320, no. 8 (2018): 792–814.

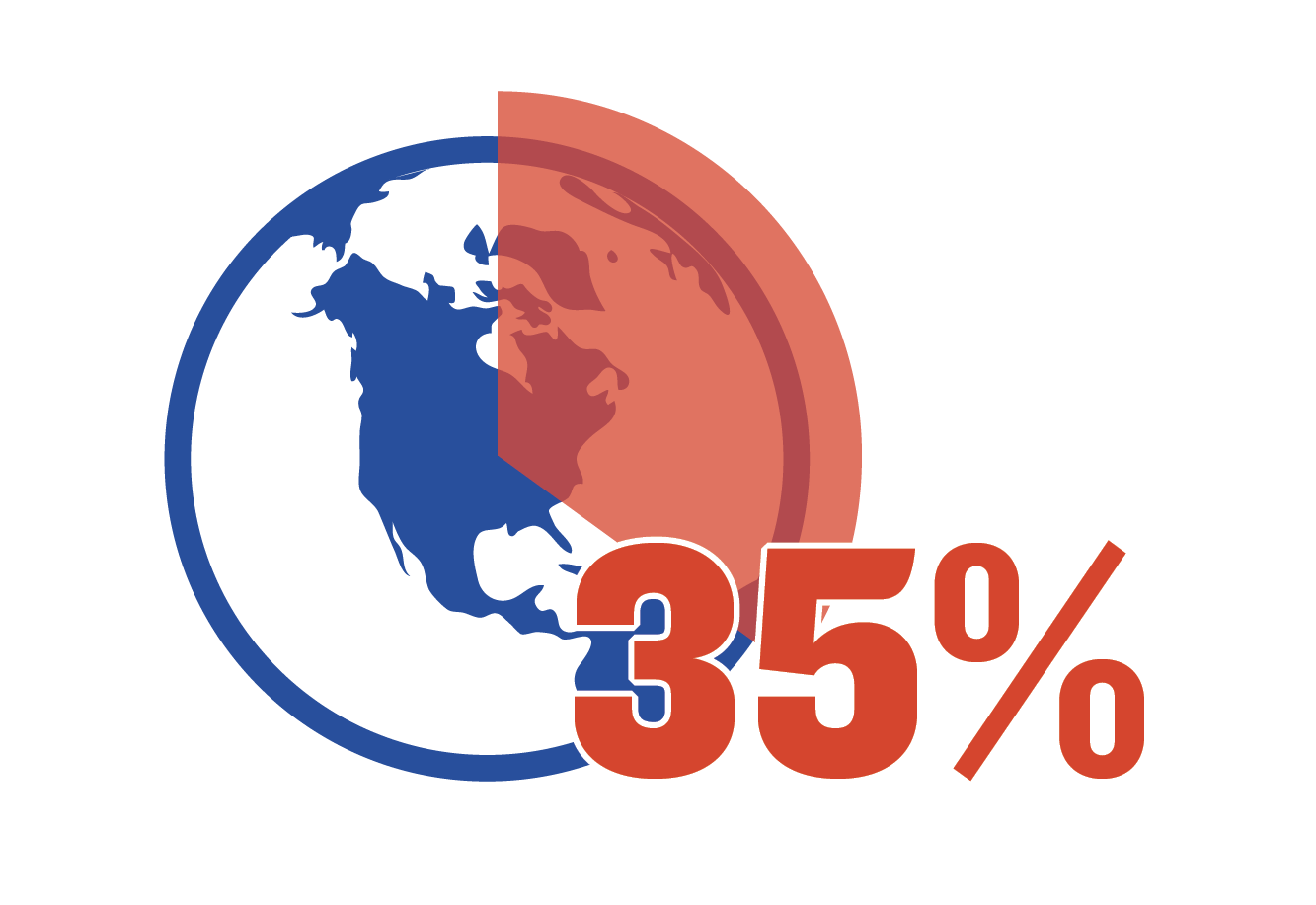

Americans are 25 times more likely to be shot to death than the residents of other high-income countries.82 Our population’s ability to easily and immediately acquire deadly weapons means that Americans of every age, race, and gender, in every state, suffer vastly higher rates of gun death and injury than people in other peer nations. Through community violence, domestic violence, mass shootings, suicides, hate crimes, and unintentional shootings, gun tragedies cause enormous loss and suffering in every community.

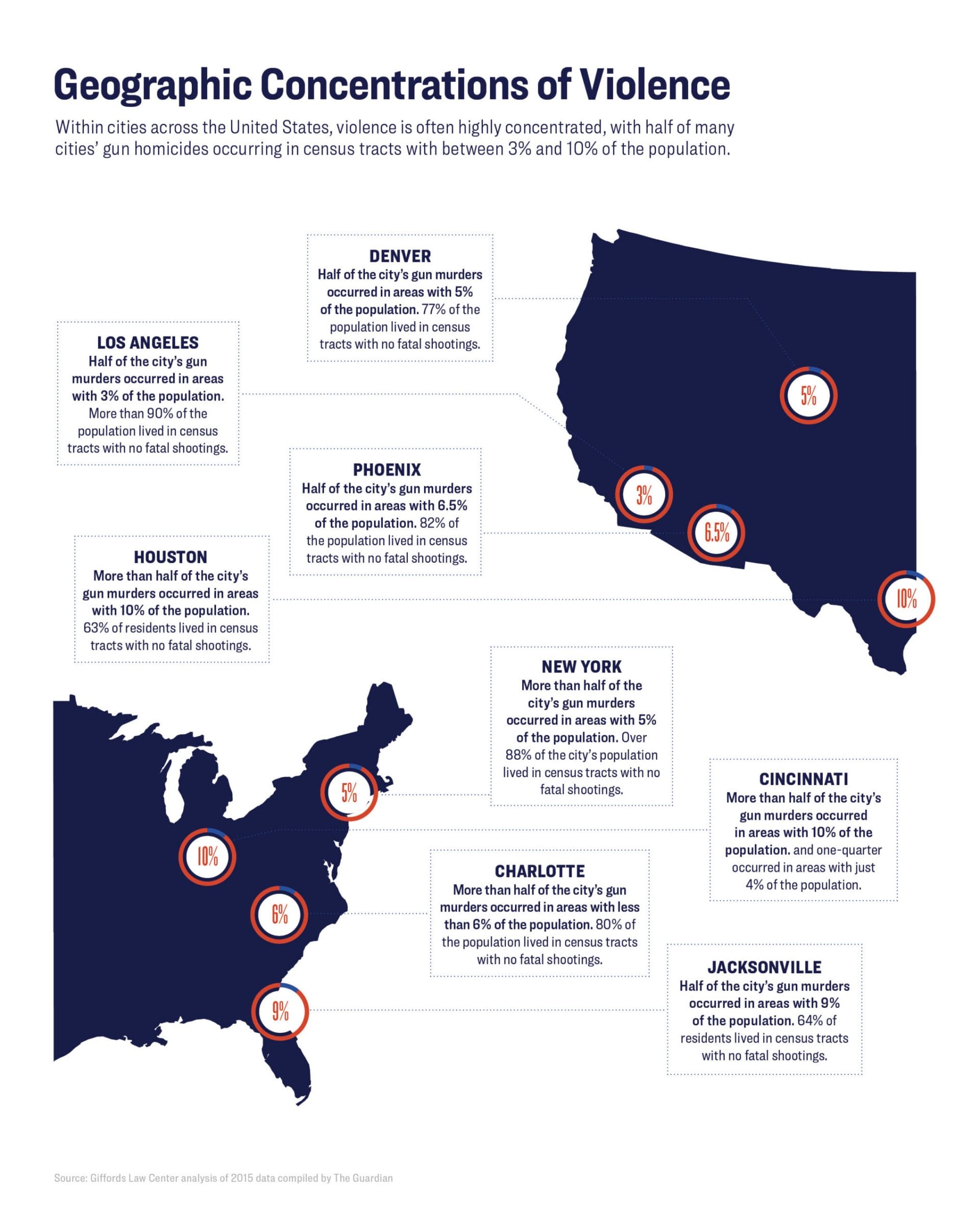

But most interpersonal gun violence in the United States is concentrated in our cities: in 2015, half of the nation’s gun homicides occurred in just 127 cities and towns.83 Within those cities, shootings concentrate much, much more in neighborhoods marked by severe poverty, disadvantage, and stark racial segregation.84 In 2015, more than a quarter of the nation’s gun homicides occurred in city neighborhoods containing just 1.5% of the US population.85 Together, those neighborhoods would cover an area smaller in size than Green Bay, Wisconsin.86

According to an analysis by The Guardian, 4.5 million Americans live in urban census tracts that experienced at least two fatal shootings in 2015.87 (A “census tract” is a geographic area designated by the US Census Bureau that is “roughly equivalent to a neighborhood” and typically encompasses between 2,500 to 8,000 residents.)88 People who lived in these areas were about 400 times more likely to be shot to death than the average person in other high-income countries.89

Many Americans don’t realize just how geographically concentrated this violence is. In recent years, political commentators have often highlighted the city of Chicago as “the poster child of [the recent] big-city homicide rise,”90 and former President Trump repeatedly compared the city to war-torn Afghanistan.91 But when it comes to gun violence, there are essentially two Chicagos.

According to Giffords Law Center’s analysis, nearly 70% of Chicago’s population lived in census tracts with zero gun homicides in 2015, while 87% lived in areas that saw no more than one.92 The remaining neighborhoods—containing just 13% of the city’s population—suffered nearly two-thirds of all gun murders in Chicago that year.93 More than half of Chicago’s fatal shootings occurred in areas with 9% of the population, and more than one-fifth occurred in areas with just 2.3% of the population.

Mapping gun violence in nearly every other American city reveals similar stark divides, with large swathes of the city reporting few or no gun homicides, and isolated pockets suffering devastating numbers of killings. In a few cities with the highest rates of violence, such as Baltimore, New Orleans, and Memphis, gun violence is more widely distributed throughout the city. In Baltimore, for instance, an astonishing 61% of residents lived in census tracts that saw at least one fatal shooting in 2015.

The same was true for 53% of people living in Memphis, and 48% of people in New Orleans. But even in these cities, most gun violence was still heavily clustered in relatively small areas. Over half of Baltimore’s gun murders occurred in areas with less than 14% of the population, half of Memphis’s gun murders occurred in areas with less than 15% of the population, and more than half of New Orleans’ gun murders occurred in areas with less than 12% of the population.

While some cities are much safer than others as a whole, this data shows that there are typically much larger disparities in violence within different neighborhoods of the same city than between different cities. This is true even in places like Chicago and Baltimore that are commonly portrayed as America’s undifferentiated “Murder Capitals.”94

The communities most heavily impacted by this concentrated violence typically share a similar history. These neighborhoods are nearly all highly segregated, low-income communities forged by past and present racial discrimination—public policies and private actions that deliberately marginalized non-white and especially Black Americans; isolated them into redlined ghettos of concentrated disadvantage; and still today often exclude them from the social, civic, and economic heart of the American city.95

Americans who live in these segregated communities have often been prevented from building generational wealth. Within living memory, Black Americans have been blocked from moving to majority white neighborhoods, obtaining home mortgages and educational loans, joining trade unions or obtaining skilled work, attending colleges or equally funded schools, and obtaining Social Security benefits.96

These neighborhood disadvantages were compounded by “white flight” to the suburbs, economic disinvestment, the disappearance of manufacturing jobs, environmental hazards like chronic lead exposure, and mass incarceration fueled by a “War on Drugs” that has been applied most broadly and severely against young Black men, a population that does not use or sell illegal drugs at a higher rate than their white peers.97 These disadvantages have persisted in the same neighborhoods for generations.98

Encumbered by the lack of a family safety net, even higher-income people of color may still struggle to afford to move to wealthier and more integrated neighborhoods.99 Research shows that Black families making $100,000 per year typically live in the kinds of neighborhoods inhabited by white families making $30,000.100 This helps to explain why Black men with postsecondary degrees are 30 times more likely to be killed by firearms than white men with similar levels of education.101

Disparate racial impact

In America, the toll of gun violence falls overwhelmingly on people of color, especially young Black men and boys and their loved ones. In 2019, violence was responsible for 5% of deaths among young white men and boys aged 15 to 24,102 13% of deaths among Indigenous or Native American men and boys, 17% of deaths among Hispanic or Latino men and boys, and nearly half, 48%, of deaths among Black men and boys in this same age group.103

BLACK AMERICANS ARE AT HIGHER RISK OF GUN HOMICIDE

Source

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2021. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html on Mar 17, 2022. Calculations were based on five years of the most recently available data: 2016 to 2020

The parents of a Black teenage boy were as likely to lose their son to violence as nearly every other cause of death combined—every medical condition, cancer, virus, and infection; every act of nature, suicide, and car crash; every drug, toxin, and opioid; every fall, fire, drowning, choking, and accident. Combined.

And that statistic is a national average: In poorer, segregated city neighborhoods where violence is most heavily concentrated, violence is responsible for even more deaths. This violence is almost exclusively gun violence. Nearly all homicides killing young Black men and boys—95%—are committed with guns.104

This violence doesn’t spare young children caught in the crossfire: Violence is the second leading cause of death for Black boys between ages 10 and 14, and is responsible for 12% of deaths among all Black children ages one to nine.105

Law enforcement officers have dangerous and often trauma-inducing jobs.106 But statistically, being a young Black man in America is even more dangerous: Black men and boys ages 15 to 24 are nearly 11 times more likely to be shot to death in a homicide than officers are to be shot and killed in the line of duty.107

Extreme murder inequality is a national phenomenon. Black men and boys comprise less than 7% of the US population but 43% of the nation’s murder victims and 51% of those murdered with a gun.108 Gun safety laws have a protective effect for all Americans, but Black Americans are still murdered in some of the nation’s safest states at a higher rate than white Americans in the most dangerous states in the country.109

There are at least 22 states where Black men are more than 10 times as likely to be murdered with a gun as white men.110 And some states have even more extreme firearm homicide disparities: from 2010–2019, Black men were 50 times more likely to be shot to death in New Jersey than white men the same age, 46 times more likely in Illinois, 39 times more likely in Wisconsin, and 31 times more likely in Michigan.111

These enormous racial disparities are even starker at the city level. As discussed above, violence within each city is geographically concentrated in certain neighborhoods and blocks. Those impacted neighborhoods are usually overwhelmingly segregated communities where the vast majority of residents—including, logically, the neighborhoods’ victims, survivors, and perpetrators of violence—are people of color.

Baltimore, for instance, saw gun homicides spike in 2015 up to what was, at that point, an all-time high.112 But in the heavily segregated city,113 predominantly white neighborhoods were “almost completely exempt from the rising violence.”114 Black men comprised 92% of the city’s gun murder victims that year.115 Similar racial disparities were evident in cities across the United States.

In Chicago, a majority of the city’s murder victims in 2016 were young Black men between the ages of 15 and 34, even though that group comprised just 4% of the city’s population.116 While these racial disparities in murder rates exist nationwide, researchers have found that they are significantly larger in more racially segregated areas, even after other markers of racial inequality are accounted for, including unemployment, poverty, income, wealth, and single-parent families.117

It should be noted that this staggering level of violence and murder inequality exists after a generation of improvements. Murder rates across demographic groups used to be even higher. From 1993 to 2014, murder rates among Black Americans fell by more than half. They also fell by 18% among Native Americans, 37% among white Americans, and a remarkable 70% and 72% among Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander Americans, respectively.118 Though murder rates have begun to rise again since 2014, Americans, and especially Americans of color, are safer today than they were a generation ago.

Despite these decades of progress, many white Americans may take for granted a degree of safety that has not been afforded to many predominantly communities of color. As leading sociologist and researcher Andrew Papachristos wrote in a Washington Post op-ed, “America’s haves and have-nots are divided not just by how much people earn, where they went to school or what car they drive, but more fundamentally by whether they feel safe when they tuck their kids in at night.”119 This safety gap is one of the starkest examples of racial inequity in America today.

CONCENTRATION WITHIN GROUPS

Because shootings are so disproportionately concentrated in isolated neighborhoods, these communities are often described in broad strokes as violent themselves. People living in the same city may see whole neighborhoods as no-go zones and hear about them only in the context of crime and disorder. The data tells a very different story. The communities most impacted by violence are not “lost zones” filled with hardened, organized killers. The most dangerous streets in America, the places abandoned and written off as “bad neighborhoods” by so many, are nearly entirely populated by law-abiding people who are survivors and victims of the violence around them, not participants.

In the most comprehensive analysis of this subject to date—a study from the National Network for Safe Communities titled The Less Than 1%: Groups and the Extreme Concentration of Urban Violence—researchers demonstrate that a majority of homicides and shootings in our cities occur among a tiny fraction of the population, even in cities with the nation’s highest rates of violence.120 Researchers looked at data from nearly two dozen cities and found that on average, at least 50% of homicides and at least 55% of nonfatal shootings involve people—as victims and/or perpetrators—known by law enforcement to be affiliated with “street groups” involved in violence.121 Researchers found that members of those groups constitute less than 0.6% of a city’s population on average.122

Within that small high-risk population, the number of people who actually perpetrate violence is much smaller still. Violence intervention experts have estimated that in an average-sized “group” involved in violence—typically involving 25 to 30 members—“generally only two or three members will reliably pick up a firearm and use it when there is a conflict.”123 Others within the group may rely on that small number of people to settle scores or defend them, but the actual number of active or would-be shooters in the average city is “far lower” than the 0.6% of the population affiliated with street groups.124 In some cities, an even tinier portion of the population are in these high-risk groups: researchers estimated that in Minneapolis, just 0.15% of city residents were involved in groups, and a small number of perpetrators within that population were connected to at least 54% of the city’s shootings.125

Some cities did have meaningfully higher rates of group involvement, especially within “city segments” (or neighborhood areas) that were most impacted by violence. The Eastern District of Baltimore, for instance, suffers some of the nation’s highest rates of violence and also had some of the highest rates of estimated street group involvement of any area evaluated by the National Network’s researchers. But even there, just 0.75% of the population was determined to be involved in street groups; individuals within that high-risk population were linked to at least 58% of homicides and at least 55% of nonfatal shootings126 in an area that has been repeatedly branded among “the most dangerous neighborhoods in America.”127

Every other study estimating the portion of the population involved with street groups has similarly found that less than 1% of the population, and less than 5% of people in younger, high-risk age brackets, are involved in street groups.128 While it’s true that violence is often geographically clustered around certain blocks, it’s critical to remember that “the blocks themselves are not committing the violence,”129 and neither are the vast majority of people living there. A majority of violence in our most impacted communities is perpetrated by a fraction of a fraction of 1% of the population.

And yet, all too often, our leaders have implemented policing and anti-violence efforts—including both punitive and preventative strategies—that treat the more than 99% of people who are not involved in groups or perpetrators of violence as if they are active participants, instead of survivors, victims, and witnesses.

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

Exploring the Jude Effect

Research is clear that community trust and engagement with law enforcement are essential for public safety. To meaningfully address cycles of violence and retaliation, law enforcement needs active witness participation and testimony, and communities need trusted guardians who can justly and effectively protect them, prevent violence, and fairly hold people, including police officers, accountable for taking or threatening human life.

The “Jude Effect” is what happens when a police force loses the trust and cooperation it needs to protect and serve effectively. When significant portions of a community give up on law enforcement as their protectors, some of the most desperate, traumatized, or alienated members of that community start taking justice into their own hands, often with impunity. The loss of trust and engagement with law enforcement fuels vigilante violence, which causes more fear, gun carrying, and retaliatory violence in turn. For too many, this is the story of gun violence in the American city.

tHE STORY OF FRANK JUDE

Frank Jude nearly lost his life outside a housewarming party in Milwaukee in October 2004.130

No shots were fired. Jude’s injuries wouldn’t appear in any analysis of gun violence incidents. But the events that transpired one October night—the particularly horrific brutalization of one young man by members of the Milwaukee police force—exacerbated a dangerous, downward spiral of distrust and disengagement that would ultimately leave many more people shot and dead across the city.131

On October 23, 2004, 26-year-old Frank Jude and his friend, Lovell Harris, accepted an invitation from two female college students to attend a housewarming party.132 The party was hosted by a member of the Milwaukee police force and many of the 25–30 partygoers in attendance were off-duty officers. The party went late into the night and, according to neighbors, involved heavy drinking.133

By the time the men and their dates arrived at the party, it was after 2:30am. They were greeted by unfriendly stares, and assumed it was because of the color of their skin. All of the other partygoers, as well as Harris and Jude’s dates, were white. Harris and Jude were not. (Harris describes himself as Black and Jude describes himself as biracial.) One of the female students with them described this as a “very uncomfortable situation,”134 so after five tense minutes at the party, the four decided to leave and returned to the truck they had arrived in.

Before they could drive away, a group of at least 10 men came out of the house and surrounded their truck. The off-duty officer who was hosting the party said his officer’s badge had gone missing from his bedroom and accused the four of stealing it. The men surrounding the truck demanded that the four get out and return the missing badge.

When the four refused to get out of the truck, the group of men threatened them and a man in the crowd broke one of the truck’s headlights. Alarmed, Harris called out to try to wake the neighbors. A man in the crowd responded: “N*gger, shut up, it’s our world.” All four were eventually dragged out of the vehicle. One of the students called 911 and said a “mob” claiming to be police officers were going through their things and trying to grab her phone.135

The group’s search did not turn up the missing badge. But instead of concluding that the host had been mistaken, court documents later noted, “the [group of] men became enraged and violent.” Events escalated quickly and brutally. One man drew a knife and cut Harris’s face before he managed to run away. Jude wasn’t able to escape. Several off-duty officers grabbed him and held his arms behind his back while others kicked and punched him. One of the students called 911 again and told the operator “they’re beating the shit out of him.” When the men in the crowd saw her on the phone, they grabbed the phone from her and flung her against the truck hard enough to dent the truck’s metal.

Twelve minutes later, two on-duty officers arrived at the scene to respond to the student’s 911 call. But instead of stopping the beating, one of the arriving officers joined in. When he was told that Jude had stolen an officer’s badge, the arriving officer handcuffed Jude136 and stomped on his face. Another off-duty officer kicked Jude in the groin. Another jammed a pen in his ears. Someone broke two of Jude’s fingers, bending them back until they snapped. The party’s host pointed a gun at Jude’s head. An officer used a knife to cut off Jude’s jacket and pants. Court documents later noted that Jude “never fought back” and had been too severely concussed to defend himself.

When additional on-duty officers arrived at the scene, they found Jude half-naked in a pool of blood. They arrested him and took him to the emergency room in the back of a police car. The admitting physician decided to take photographs of Jude’s injuries because they were too extensive to document in writing.137 The missing police badge was never found. A judge later surmised, “perhaps [the party’s host] had put down the badge in the house and was too soused to remember where.”

Elsewhere in Milwaukee that night, there were other officers performing just and effective policing work to protect and serve the city’s residents. Their work often put them in harm’s way: A young Milwaukee officer was shot to death that same week during an armed robbery outside a gas station.138 But those officers’ work—and community safety across Milwaukee—was undermined in profound ways by the officers who brutalized Frank Jude, and by an ensuing response that was widely perceived to be unconcerned with the dignity and safety of people of color.

A picture of Frank Jude’s bloodied, misshapen face hit the papers a few months later, in February 2005, when the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel broke the news about the beating.139 The paper published a disturbing photo that an emergency room physician had taken of Jude’s injuries, along with detailed descriptions of his wounds. The news report also documented prosecutors’ failure, up to that point, to charge any officers suspected in the beating.140

More than 100 people protested in front of the district attorney’s office four days later, many of them carrying signs alleging a cover-up by the police department.141 Three months after the beating, investigating prosecutors still had not spoken with Jude’s friend, Lovell Harris, a key witness to the events of that night.142 And multiple officers were refusing to answer questions about the events they had witnessed or participated in.143

A month later, the city’s police department dismissed nine officers and disciplined four others in connection with the beating.144 But an all-white jury subsequently acquitted the party’s host and two other officers of all criminal charges in state court.145

After thousands of people protested outside the courthouse, federal prosecutors brought civil rights and obstruction charges against eight of the officers and won convictions against seven.146 Two of those officers tearfully apologized to Jude in court. One, who admitted to stomping on Jude’s head while in uniform, cried as he told Jude, “I should have done more to protect you that night.”147

A cycle of distrust and violence

“When Frank Jude’s face hit the papers in Milwaukee, the cops’ phones stopped ringing.”148

This story is one of an exceptionally horrific instance of brutality against one man. But Frank Jude’s injuries were not his alone; they had devastating ripple effects across much of his city.

In 2016, a team of researchers from Harvard, Yale, and Oxford published a groundbreaking study documenting the impact that Jude’s beating had on public safety in Milwaukee.149 The researchers found that news of the event intensified a longstanding gulf in trust between Milwaukee’s residents and their police force, and triggered a dramatic and dangerous decline in citizen crime reporting.

Researchers found that after news of Jude’s beating broke in February 2005, there was a nearly 20% drop in 911 calls reporting crimes to the Milwaukee police, driven by a much steeper decline in calls reporting violent crimes from the city’s Black community.

The heavily segregated city150 saw a small decline in 911 calls from predominantly white neighborhoods for a few weeks after the story broke, but this effect “dissipated rapidly.” By contrast, the declines in crime reporting from predominantly Black neighborhoods were “large and durable,” lasting more than one year.

In total, researchers estimated that Milwaukee’s residents placed at least 22,000 fewer 911 calls reporting crimes to the police in the year after they learned about the beating of Frank Jude. A majority of these 22,000 “missing” 911 calls were from neighborhoods where at least 65% of the population was Black.

The researchers also concluded that this number likely substantially underestimated the true number of missing 911 calls because this estimate was based on the number of calls the Milwaukee police force would expect to receive in a normal year, based on previous crime trends.

But the year following the Frank Jude beating was not a normal year for crime in Milwaukee. The city’s large reduction in 911 calls occurred alongside a significant spike in violence. Homicides in Milwaukee jumped by one-third in the summer of 2005. The city would not experience a deadlier year for murders for another decade, until 2015,151 following reports that a Milwaukee police officer shot and killed an unarmed Black man during a mental health welfare check amid a disturbing spate of other highly publicized police brutality cases nationwide.

Researchers called this observable decline in proactive citizen cooperation with law enforcement “the Jude Effect.” The study’s authors concluded that “publicized cases of police violence not only threaten the legitimacy and reputation of law enforcement; they also—by driving down 911 calls— thwart the suppression of law breaking, obstruct the application of justice, and ultimately make cities as a whole, and the black community in particular, less safe.”

While often overlooked by the public and policymakers, the primary implication of the Jude Effect study—that there is a strong link between community trust and firearm violence—has been documented by many other researchers, and for a long time.

In 2011, research supported by the National Institute of Justice sought to examine why high murder rates had persisted and even spiked in certain Chicago neighborhoods that were experiencing declines in poverty, even as rates of violence were falling across most other neighborhoods in the city.152 The researchers found strong evidence that “neighborhoods where the law and the police are seen as illegitimate and unresponsive have significantly higher homicide rates,” even after accounting for differences in race, age, poverty, and other structural factors.153 These effects were not driven by a complete neighborhood consensus; most communities hold a spectrum of views about law enforcement, with young people, men, and people of color tending to report more distrust, and older adults, women, and white Americans less distrust.154 But neighborhoods that have the most significant levels of distrust of law enforcement on average were found to have much higher and more persistent rates of violence, even after controlling for other factors.155

Decades ago, leading sociologists demonstrated that the retributive “code of the street,” involving cycles of violent vigilante justice, is actually an “adaptation to a profound lack of faith in the police and the judicial system—and in others who would champion one’s personal security.”156 They observed that this code “emerges where the influence of the police ends and personal responsibility for one’s safety is felt to begin,”157 and that “when the law is perceived to be unavailable—for example, when calling the police is not a viable option to remedy one’s problems—individuals may instead resolve their grievances by their own means, which may include violence.”158

When people don’t view calling law enforcement as a reliable tool for resolving disputes or holding others accountable for wrongdoing, they can fall into a “paradox,” where some individuals who believe in the substance of the law and oppose violence are nonetheless propelled toward violence as a form of self-reliance or vigilante justice.159

Victims of violence are especially likely to fall into this paradox: researchers evaluating variations in homicide trends across different Chicago neighborhoods found that violent victimization had a “dramatic” negative effect on people’s views about law enforcement and its role in the community.160 People who have been shot are especially unlikely to trust the police to keep them safe, particularly since, as discussed below, police departments usually fail to arrest the people who pulled the trigger. Victims of violence are then much more likely to be involved in cycles of retaliatory violence as both shooters and repeat victims.

This is why so many urban hospitals and trauma centers see a “revolving door” of gunshot injury: Studies have long shown that in many of these hospitals, over 40% of patients treated for violent injuries such as gunshots return to the emergency department with new violent injuries within five years,161 and as many as 20% are killed within that short time frame.162

In other communities, these victims and their loved ones may be more likely to press law enforcement agencies to arrest their assailant, file a civil lawsuit, or move away from distressing circumstances. But when the formal justice system is seen as absent, abusive, or ineffective, a small number of individuals are compelled toward violent vigilantism instead.

iStock

Over-Policing and Under-Protection in America’s Cities

In March of 2019, The New York Times Magazine published an in-depth report on “The Tragedy of Baltimore,” exploring the city’s nearly unprecedented spike in murders.163 The report ended with a scene from a community meeting in a school auditorium where Baltimore’s new police chief was introducing himself to residents of a neighborhood especially hard hit by the surge in violence.

An hour into the meeting, a woman stepped up to the microphone to describe how “bewildering” it had been to accompany a friend near a safe and tourist-friendly neighborhood downtown:

“The lighting was so bright. People had scooters. They had bikes. They had babies in strollers. And I said: ‘What city is this?’ … Because if you go up to Martin Luther King Boulevard … we’re all bolted in our homes, we’re locked down … All any of us want is equal protection.”

As the New York Times piece concluded, “the residents streaming into these sessions … were not describing a trade-off between justice and order. They saw them as two parts of a whole and were daring to ask for both.”164

But for many communities of color, law enforcement and the justice system impose enormously unequal harms while also failing to provide equal protection from and accountability for violence.

The recent public discussion around criminal justice reform has highlighted the many ways in which communities of color, especially Black and Indigenous communities, have been inequitably policed and incarcerated on a mass scale for generations. As The Sentencing Project describes, “Like an avalanche, racial disparity grows cumulatively as people traverse the criminal justice system … Once arrested, people of color are also likely to be charged more harshly than whites; once charged, they are more likely to be convicted; and once convicted, they are more likely to face stiff sentences – all after accounting for relevant legal differences such as crime severity and criminal history.”165

Multiple studies have found that police are more likely to stop and search Black and Hispanic people than their white peers, even though searches of Black and Hispanic drivers are less likely to turn up contraband.166 According to one estimate, 80% of Black 16- and 17-year-olds were stopped by the New York City Police Department in 2006, compared with 38% of Hispanic and 10% of white teens the same age.167 And though Black and white Americans use and sell drugs at similar rates, Black Americans are nearly three times as likely to be arrested for drug offenses, and at the state level, 6.5 times as likely to be incarcerated for such crimes.168

The collateral impacts on families and communities are hard to overstate. Data published in 2009 indicated that a Black man without a high school diploma had a nearly 70% chance of being incarcerated at some point by his mid-thirties,169 perpetuating a generational poverty trap for millions.170 And though people of color are disproportionately represented among crime victims, they are also often underserved by publicly funded crime victim assistance programs.171

Regardless of the motivations or values systems of individual actors within law enforcement or the criminal justice system, the cumulative effects of these disparities are enormous, and create a system of justice that is frequently experienced as untrustworthy, abusive, racist, or illegitimate in communities of color.

At the same time, amid this vast, sometimes brutal police presence in segregated city neighborhoods, the most serious crimes imaginable—murders and attempted murders—are a pervasive cause of death, and typically go unpunished. A recent in-depth investigation by The Washington Post found that across 52 of the nation’s largest cities over the past decade, 53% of all murders of Black Americans never led to an arrest, let alone a conviction.172 Nearly three-quarters of all unsolved murders in these cities involved a victim who was Black.173

Other investigative reporting has indicated that our justice system and law enforcement are even less likely to provide accountability for murders and attempted murders involving a gun: Researchers for The Trace found that across 22 cities, 65% of fatal shootings involving a Black or Hispanic victim never led to an arrest.174

Police also failed to make an arrest in nearly 80% of nonfatal shooting incidents involving Black victims.175 These are citywide averages; in the poorest and most disadvantaged communities within those cities, accountability for shootings and murder is even rarer still.

This lack of accountability is no secret in communities most impacted by violence. When the Urban Institute surveyed young people from Chicago neighborhoods with the highest rates of homicide, only 14% said they thought a person was likely to “get caught” for shooting at someone in their neighborhood, and that number was even lower among young people who said they had carried a gun before.176 Unsurprisingly, just 13% said police in their neighborhood were effective at reducing crime.177

This “near-total impunity for homicides and shootings in distressed communities” is a major driver of community distrust and community violence, as it “signals that the state can’t or won’t actually protect people from the most significant harm. Where that’s true, people feel the need to protect themselves and settle disputes through other means, including private violence.”178

It should be noted that arrest rates are surprisingly low for murders and shootings of white victims too, although arrest rates are substantially higher for white victims than they are for Black victims in nearly every city.179 When the criminal justice system fails white victims, though, their families are on average more likely to have the resources they need to move away and put distance between themselves and circumstances that might otherwise make conflict and retribution more likely.180 They may also have a stronger baseline of positive previous interactions and trust in their local law enforcement and the criminal system.

People with lower levels of wealth, job security, and privilege are more likely to have had prior negative experiences with law enforcement and are also more likely to be trapped in the same invisible walls of poverty, segregation, and circumstance as the people who wronged them or their loved ones. As a result, vigilante justice breaks out more often within those invisible walls, particularly when victims know they are unlikely to see their loved ones’ killers arrested and are unlikely to be arrested themselves for committing retributive violence.

As a spokesman for the Baltimore Police Department acknowledged, “Today’s victim is yesterday’s suspect, and today’s suspect can be tomorrow’s victim.”181 And as The Baltimore Sun observed, “Cases that aren’t cleared by police are too often cleared by the streets, leading to the type of reciprocal killings that plague [the city].”182

In this regard, the perceived harshness of the American justice system and its inability to protect people from violence are both taken as evidence that law enforcement and society at large are untrustworthy and, at best, indifferent to the wellbeing of people of color—especially young Black men. Crime reporter Jill Leovy summarizes this dynamic: “Our criminal justice system harasses people on small pretexts but is exposed as a coward before murder. It hauls masses of Black men through its machinery but fails to protect them from bodily injury and death. It is at once oppressive and inadequate.”183 Leovy suggests to readers:

Imagine that you’re a student at a school. There are bullies at the school, and the bullies beat you up every day on the playground. But the only time the playground supervisor comes around, he or she says, “Don’t chew gum on the playground,” and walks away, and ignores the bruises and the fighting. You would be cynical. You would cease to believe in the system. In fact, you’d probably cease to believe that it’s just the bullies picking on you, but rather that the system is a bully in and of itself.184

The real-world facts bear out this analogy tragically often. A 2019 investigatory report by the Trace found that since 2001, the Chicago Police Department had made more than 600,000 arrests for possessing or purchasing drugs, including marijuana, while also “fail[ing] to make an arrest in 85 percent of the violent crimes committed with firearms.”185 A Chicago mother grieving the loss of two sons to gun violence explained to reporters that in her community, “They’ll get a person for marijuana before they’ll get a person for murder.”186

Nationally, violence kills more young Black men than almost every other cause of death combined, but our nation’s law enforcement agencies arrest more people for possessing personal quantities of marijuana than for all violent crimes combined.187

This is partly a function of where law enforcement agencies choose to direct their time and resources: from January to June 2020, police officers in New Orleans, a city with one of the highest homicide rates in the country, spent just 0.7% of their time on average responding to homicides and nonfatal shooting incidents.188

People of color are stopped and searched more, arrested more, charged more, and sentenced for longer,189 and are substantially less likely to see justice done when a loved one has been shot or killed.190 The same justice system that fails to arrest the killers of a majority of Black murder victims still hauls millions behind bars for non-violent offenses and is often not held accountable when police officers perpetrate crimes or violence themselves.

These dynamics are further exacerbated by the fact that in cities across the country, people of color are commonly policed by officers who do not live in their community and do not reflect their community’s racial or ethnic makeup. Across the 75 cities with the largest police forces in the United States, on average, 60% of officers (and 65% of white officers) reside outside the limits of the city they serve.191 And according to Giffords Law Center’s analysis of data from 269 of the nation’s largest police departments, in 57% of departments, people of color were represented on the police force at less than half their share of the city’s population.192

Researchers have also found that police departments are much more likely to rely on revenue-driven policing in communities of color. In cities with larger Black and Brown populations, police officers are more likely to ticket and fine community members to fund their own operations, and in doing so, can criminalize poverty when they arrest those same residents for failure to pay.193

Law enforcement agencies are also more likely to utilize civil asset forfeiture—whereby law enforcement agencies may confiscate and sell property they believe to be connected to a crime even in cases where the owner is not charged with any offense—when local unemployment rates increase, suggesting that policing for profit increases when economic distress in the community makes budgets tight.194 People of color often bear the brunt of these seizures.195

Unsurprisingly, researchers have also found that in cities that collect a greater share of their revenue from these fines and fees, police departments solve violent crimes at significantly lower rates.196 And cities that solve fewer homicides have much higher rates of homicide on average.197